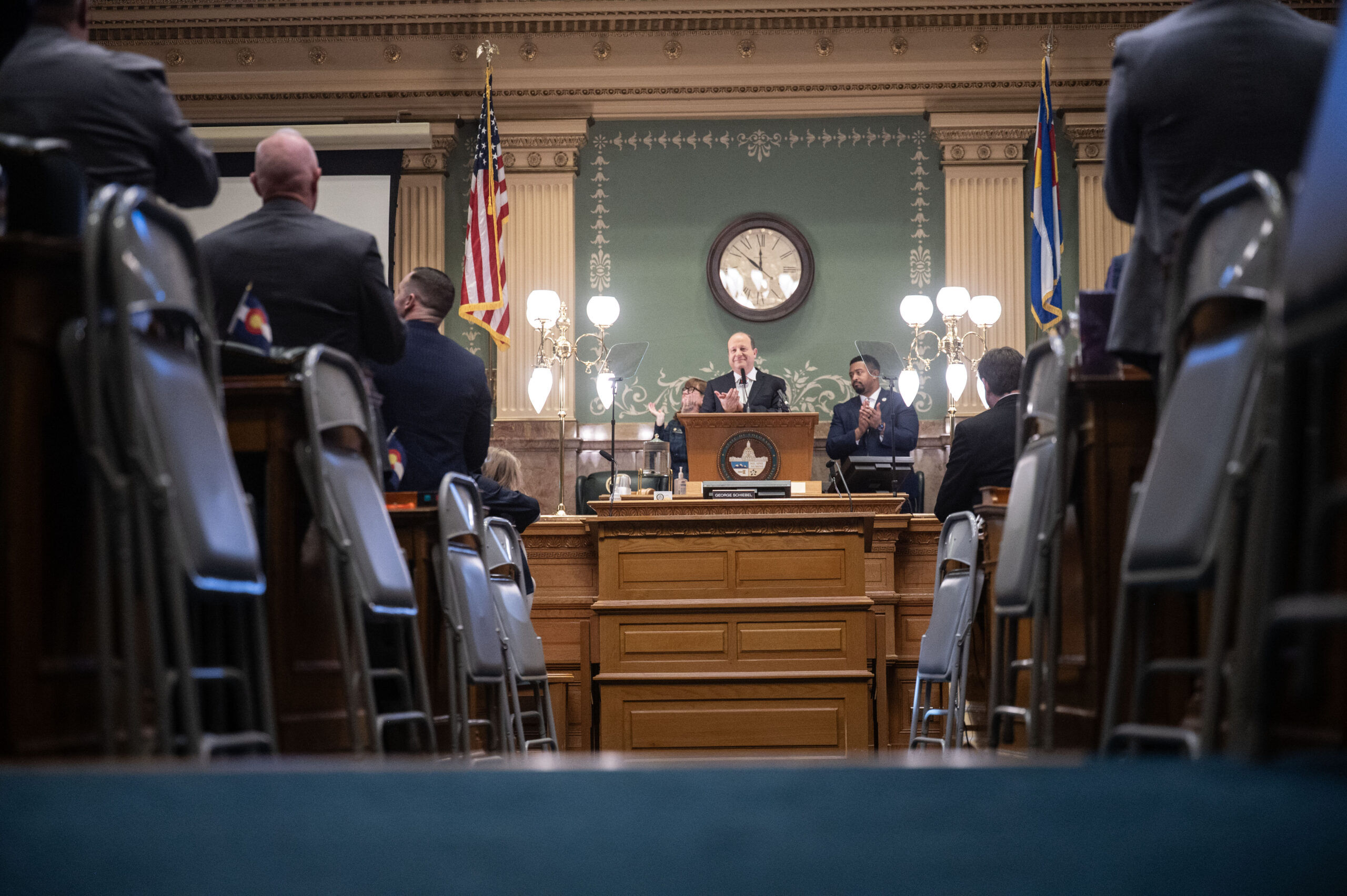

Colorado governor insists local officers can work with DEA agents amid non-cooperation law

Gov. Jared Polis on Friday insisted that local law enforcement officers in Colorado can — and should — work with federal drug enforcement authorities to go after criminal activity.

An official of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency earlier said Colorado’s “sanctuary” laws, notably its prohibition against cooperating with federal authorities on illegal immigration matters, are having a “chilling effect” on law enforcement’s ability to pursue drug cartels operating in the state.

“There’s always a matter of making sure local line officers are educated in our laws and that they know that they’re able to work with our federal partners on criminal matters,” Polis told The Denver Gazette. “So, it doesn’t shock me that there are some line officers somewhere that didn’t know they’re able to work with law enforcement federally on criminal investigations.”

“But, generally, we hope our sheriffs and our police chiefs are doing a good job, making sure that we can work closely with our federal partners. I’ll be happy to talk to them,” he added. “So, I’ll set that up.”

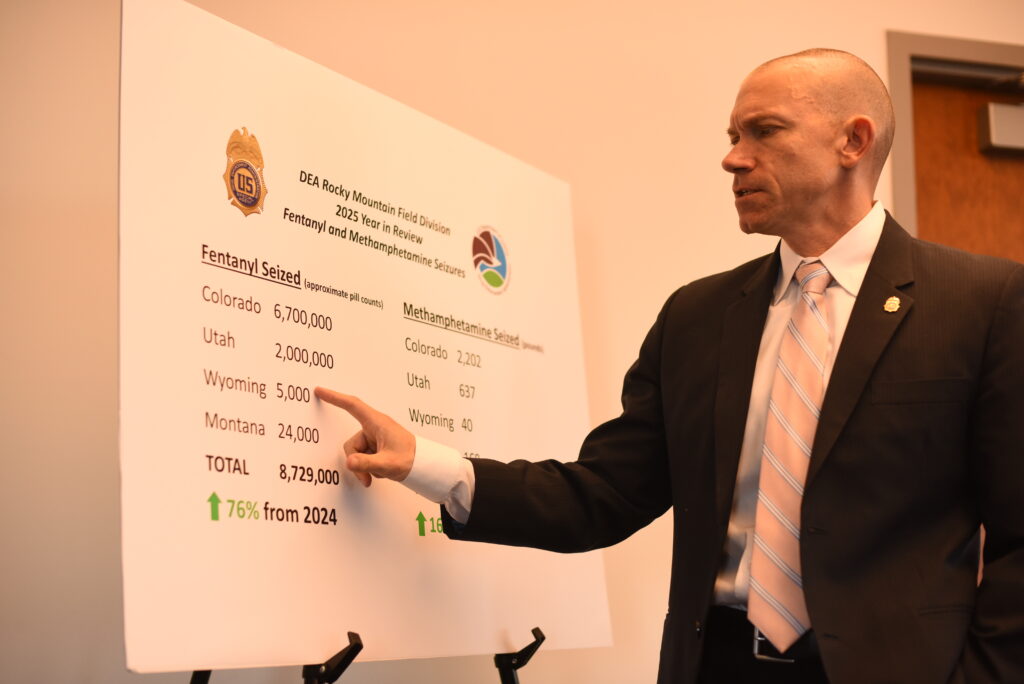

David Olesky, the special agent in charge of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) Rocky Mountain Field Division, earlier said that local law enforcers are hesitant to even ask for standard information, such as the name and date of birth of those possibly affiliated with drug activity, out of fear their action could later be used against them by their own state.

“Local and state authorities are fearful that the state is going to come back to them — that the passing of their information, even though it originated in drugs, is going to cause civil liability, where they can get sued up to $50,000,” Olesky said.

On May 23, Polis signed into law Senate Bill 25-276, which, at its core, reemphasized existing state law that precludes local law enforcers from detaining an individual based on an “immigration detainer.”

State statutes already prohibit an employee of a state agency from disclosing any identifying information of a person to assist with immigration enforcement. The new legislation extended that to employees of all political subdivisions, such as “home rule” counties and municipalities. The law, which imposes a civil fine of $50,000 for each violation, includes an exemption for criminal investigations.

Backers of the non-cooperation law have long argued that Colorado’s local police officers should not be commandeered to conduct the work of federal immigration authorities. Others have raised worries about violating due process rights for immigrants living illegally in the country who might be swept up in the Trump administration’s illegal immigration crackdown.

Critics of the “sanctuary” statutes, meanwhile, countered that they made it more difficult for local law enforcement to work with federal agents to interdict crime, and that, ultimately, negatively affects residents, whether they are in the country illegally or not.

Colorado’s drug “sanctuary” label comes amid rising tensions between local and federal law enforcement in Colorado, especially after Attorney General Phil Weiser filed a lawsuit against a Mesa County sheriff’s department deputy for providing a woman’s personal information to federal officials during a traffic stop.

The woman arrested, a University of Utah student, was born in Brazil, came to the U.S. under a tourist visa when she was 7, and has been living in Utah for 12 years. She overstayed her visa about a decade ago and has a pending asylum case.

A Mesa County judge dismissed the case after the sheriff’s deputy resigned from his position and promised not to work for another law enforcement agency in the state, according to local news reports. The deputy, along with several other officers, had been placed on unpaid leave and reassigned from a drug task force.

Court documents and an investigative report into the case had offered glimpses into how local and federal agents interact along America’s major corridors.

Notably, the practice of sharing information about interdictions to other agencies appeared routine, and, when the subject of a police stop is in the country illegally, immigration agents showed up to detain the individual, according to the documents.

But that practice of information sharing — a sore point of contention in other parts of the state, notably in Denver, whose political leaders had perennially balked at cooperating with immigration agents unless the case is criminal in nature — is evolving, particularly following the passage of Colorado’s latest law.

Already, the Colorado State Patrol said it will stop communicating via a Signal chat channel shared by local officers and federal drug and immigration agents.

Last month, Olesky, the DEA agent, said Colorado’s approach toward crime and illegal immigration has changed over the years.

“(Cartel members) said Colorado es un santuario … Colorado is a sanctuary,” he said. “They know Denver es un santuario. If they get arrested by the feds here, they know they will go. But if they get arrested by the state, their immigration status means nothing.”

Of particular worry to Olesky is that Denver is “on the verge of breaking” drug activity records, while the rest of the country is headed in the other direction.

Polis once anew rejected the label “sanctuary state.”

“In our state, we share criminal information with our federal partners nearly every day in some way, shape, or form. And whether the suspects are here legally or illegally doesn’t matter,” he said. “We’re fully able to cooperate on apprehending suspects, whether their presence here is legal or illegal.”

The Rocky Mountain region saw record-breaking amounts of fentanyl pills and methamphetamines seized in 2025, according to DEA officials. The seizures — a 76% increase compared to the year before — accounted for 6.7 million, or over 14%, of the 47 million pills seized by the DEA throughout the U.S., federal authorities said.

Meanwhile, fatal fentanyl overdoses in Denver rose by nearly 25% last year to the second-highest total in the past half-decade: 346 people died, up from 277 the year before.

Reporters Michael Braithwaite, Marianne Goodland and Luige del Puerto contributed to this article.